In business, we are taught to manage systems, P&Ls, and teams. But as Peter Drucker famously noted, the most difficult person you will ever have to manage is yourself.

I recently attended a panel at the Peter Drucker Forum titled “The New Sciences of Managing Yourself.” The speakers, ranging from F1 performance experts to global CEOs, all landed on a singular, striking truth: High performance is not a business strategy; it is a physiological and psychological state.

If you want to lead in a turbulent world, you have to start in the driver’s seat of your own mind.

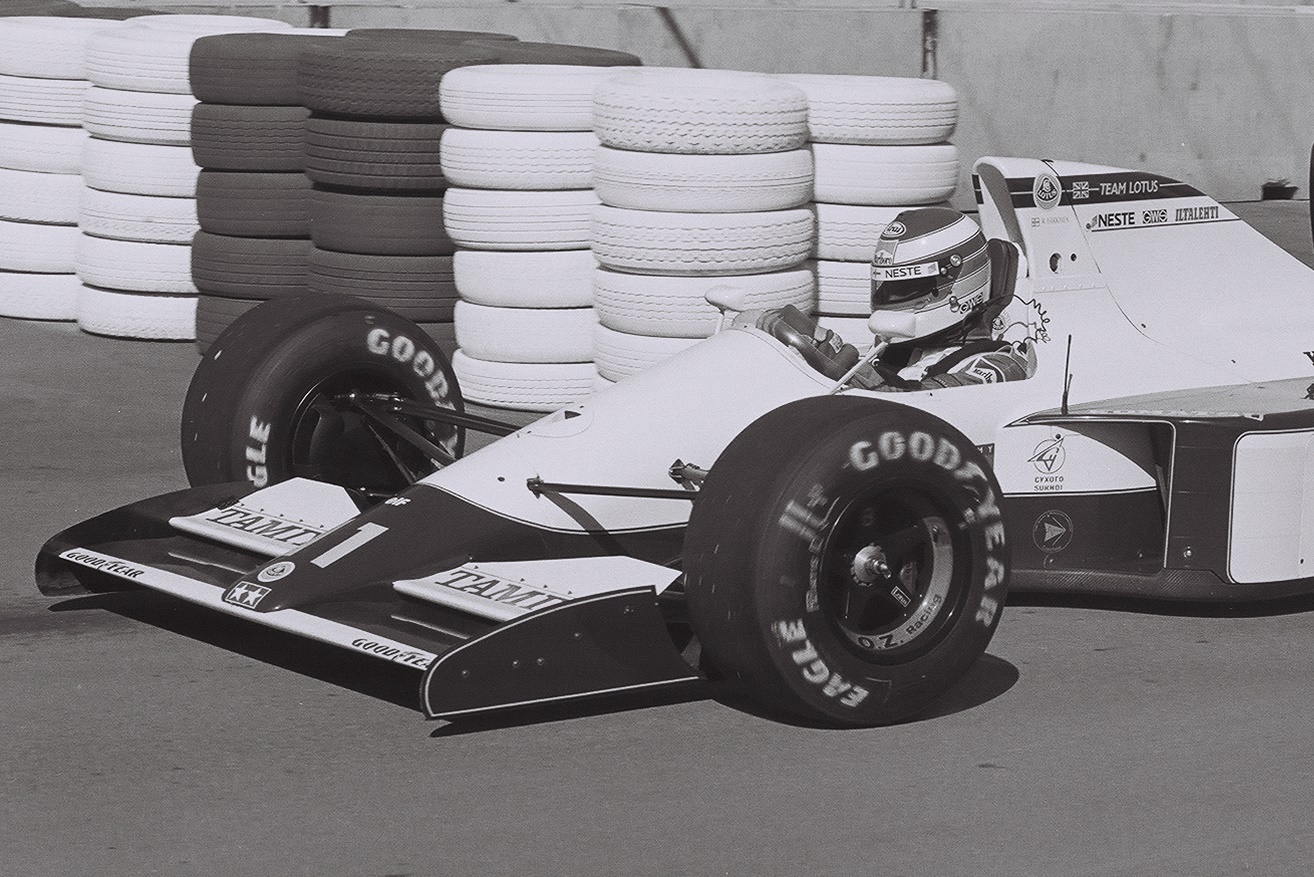

The F1 Principle: Recovery is Performance

Annastiina Hintsa (CEO, Hintsa Performance) works with 60–70% of the F1 paddock. Her secret? She doesn’t just ask drivers how they drive; she asks them who they are when they aren’t driving.

- The Identity Trap: If your identity is 100% tied to your title (CEO, Manager, Founder), a setback at work becomes an existential crisis. To survive high pressure, you need pillars of identity outside the office.

- The Pit Stop Mentality: In F1, you don’t stop because the car is broken; you stop to ensure it doesn’t break. Hintsa argues that sleep, nutrition, and mental energy are not “perks”: they are the prerequisites for the split-second decision-making leadership requires.

The Brain’s Verdict: Fear vs. Readiness

Eva Asselmann (Professor of Psychology) reminded us that our brains treat failure like social rejection. When the “internal alarm” (the amygdala) fires, we freeze.

- Action Shapes Belief: Don’t wait to feel confident before you act. Self-efficacy, the belief that you can handle what’s coming, is built by doing.

- The Story Matters: Your body feels the same during fear as it does during excitement (racing heart, sweaty palms). The elite leader reframes the story from “I’m scared” to “My body is pumping up to meet this challenge.”

The Leader’s Daily “Micro-Toolkit”

Niren Chaudhary (Former Chair, Panera Brands) shared six daily habits to bridge the gap between “knowing” and “leading.”

- The Three Marbles: Carry three imaginary marbles into every meeting. Every time you speak, you lose one. Use them wisely to create space for your team to grow.

- Learn and Love AI: Spend 30 minutes daily playing with AI. It’s not an end, it’s a means to stay curious.

- Choose Courage over Noise: When the world feels chaotic, ignore the macro-noise and ask: “What can I control in my immediate community today?”

- Practice “Wicked” Goals: SMART goals are for maintenance. WILD goals (Wicked, Illogical, Disruptive) are for transformation.

- Build Grit in the Small Stuff: Do the extra five minutes on the treadmill when you want to quit. That’s how you train for the board room.

- The Compassion Multiplier: Trust = (Competence + Character) x Care. Showing you care is the ultimate force multiplier.

Final Thought: The Diamond of Life

Niren closed with a beautiful metaphor. Life is not a flat marble; it is a diamond with many facets: work, family, health, and service. A leader who only shines in one facet is dimmed. To lead well is to do justice to the whole diamond.

Sustainable performance isn’t about running faster. It’s about knowing when to make a pit stop to finish the race.

Next Step for You: Pick one “WILD” goal for this month, something that feels slightly impossible. How would your approach change if you started at “impossible” rather than “achievable”?

Picture by Stuart Seeger from College Station, Texas, USA – Mika’s Lotus Debut, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5495395