I was engaged recently in a passionate conversation ignited by a simple comment: “A team has to be managed.” The comment made me think I wasn’t on the same page as my interlocutor.

I was discussing the importance of designing organizational roles that won’t become bottlenecks (roles that won’t prevent the organization from delivering efficiently or to adapting quickly to changes). In classic organization design, we tend to think that designing boxes on an organizational chart and putting great people in charge will solve all our problems. That approach could work in static environments, where what you have to deliver is defined once and for all.

But if your environment is continually changing, you need to adapt your value proposal to those changes. Your organization needs to be adaptable.

My interlocutor was on the path to designing the boxes of a new organization. On his radar were managers that will have full responsibility for certain groups and team leaders with full responsibility of the teams making up those groups. Static groups, static roles, static functions.

But you can’t achieve a capacity for adaptability in your organization if you rely on overloaded people dealing with multiple responsibilities. I suggested an alternative: Self-organizing teams designed around roles that are not bottlenecks, roles that team members could take either full-time or for a portion of their time.

Unfortunately, my interlocutor jumped to the conclusion that my goal was to remove all managers and team leaders from the organization—as if self-organizing teams and management were somehow mutually exclusive.

Not exactly.

Managing the self-organizing team

The Open Organization Definition lists five characteristics as the basic conditions for openness:

- Transparency

- Inclusivity

- Adaptability

- Collaboration

- Community

I’ve recently discussed the importance of making work visible when attempting to achieve transparency and collaboration at scale. Here, I’m more concerned with adaptability—creating teams without single points of failure, teams better able to adjust to changing conditions in dynamic environments.

I agree that a team has to be managed, and I think many of the activities we see as the sole responsibility of the managers or the team leaders could, in fact, be delegated directly to the team—or to team members that could effectively deliver the activities serving the team.

So from my perspective, a team has to be managed, but a large part of that management could be done by the team itself, creating a self-managed team.

Let’s review some of those activities:

- understanding the business and the ecosystem the organization evolves in

- understanding why we provide solutions, products, features, services and formulate a clear vision

- defining what needs to be delivered and when it should be delivered

- determining how it will be architected

- identifying how it will be implemented

- defining how it will be documented, demoed, tested

- distributing the work between the team members

- delivering the work

- implementing the documentation, testing

- presenting the demo

- collecting the feedback from users and stakeholders

- ensuring that the result of the work is continuously flowing to the customers or users ensuring that testing is automated and triggered for each and every change

- improving the way the team is working and increasing its impact and sustainability

- improving the efficiency of the larger system formed by the different teams

- supporting customers and partners who use the product

- fostering collaboration between users, customers, and partners in the defining and implementing the product or service

- defining the compensation of team members

- controlling the performance of team members

- supporting and developing people in the team

- hiring people

When I look at those activities, I see some that could be delegated to a system put in place by the team itself—like the distribution of work, for example. The distribution of the work can be made obvious for team members by simply making the work visible to everyone.

I also see activities that are difficult to move away from managers, like managing the compensation of team members (because it would require building a compensation system that’s more transparent, which is difficult when you don’t start from scratch due to preexisting discrepancies in the compensation of people).

I see activities that are focused on users and the why and what the team is delivering. On some teams with which I’ve worked, those activities are delegated to a team member taking, for example, the role of User Advocate or Product Owner (to use the Scrum terminology).

I see activities that are focused on how the team is working. Those activities are delegated to a team member taking, for example, the role of Team Catalyst or Scrum Master.

In both cases, their role will be to ensure that the activities are done by the team, not necessarily to handle everything by themselves.

By looking at the activities in more detail, I can envision many of them being handled by team members as part of their current role, or in a new role.

Giving managers or team leaders the ability to consider the activities for which they’re accountable and the activities they can delegate to the team can remove the bottlenecks and single points of failure that currently exist in some organizations.

Which activities in your organization could a self-organized team handle best? What have I left off my list? I’m interested interested in hearing from you.

The post was originally published on opensource.com on August 14, 2018.

One year and a half ago, I noticed that my daughter was using an app to improve her Spanish and her English. Of course, there is an app for that! There are even several apps!

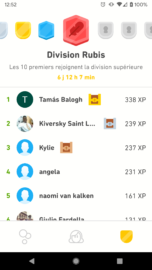

One year and a half ago, I noticed that my daughter was using an app to improve her Spanish and her English. Of course, there is an app for that! There are even several apps! Of course, with 300 million learners, you can imagine that there are several “bronze,” “silver,” “gold” divisions running in parallel. But it seems it does not affect the behavior of the learners. I realized quickly my habit of doing three lessons per day got me immediately to the top of the first divisions, but after a few weeks, it was harder to get to the top 10, and I needed to increase my practice. So, it worked… And now, to stay in the current division, I need to do a little bit more than three lessons a day.

Of course, with 300 million learners, you can imagine that there are several “bronze,” “silver,” “gold” divisions running in parallel. But it seems it does not affect the behavior of the learners. I realized quickly my habit of doing three lessons per day got me immediately to the top of the first divisions, but after a few weeks, it was harder to get to the top 10, and I needed to increase my practice. So, it worked… And now, to stay in the current division, I need to do a little bit more than three lessons a day.